|

by Dark Watcher |

|

|

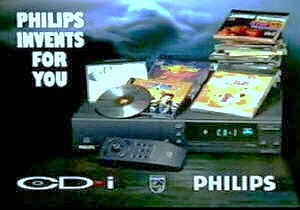

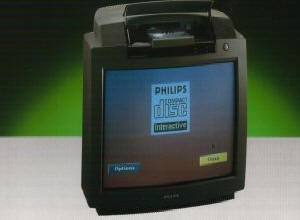

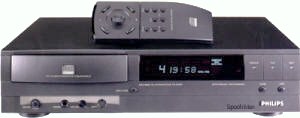

In the mid 1980s Philips and Sony partnered up to create a new CD standard containing interactive combinations of sound, images and

computer instructions. This CD standard also required specific types of players. In 1991 Philips created the Philips CD-i

210 as a multimedia system capable of playing Interactive CD-i software discs, Audio CDs, CD+G (CD+Graphics), VCDs (Video CDs) and

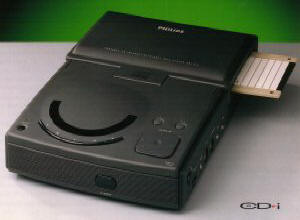

Karaoke CDs. You could essentially enjoy different types of media on the same machine. People were not quite ready for the multimedia experience and clung to their VCRs, home computers and video game consoles. With dwindling sales and the videogame market doing well, Philips decided to reintroduce the machine as videogame console. The Phillips CD-i 450 was designed to look more like a console and included a pack-in game called Burn Cycle. |

|

|

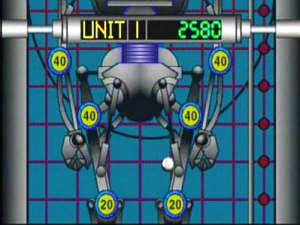

The CD-i 450 still had a high price tag and the lack of quality games prevented the CD-i from becoming competitive in the videogame

market. The console died a slow death in the late 1990s with the release of far more popular CD based consoles. FACT: Nintendo had initially planed to release a CD based add-on for its SuperNes console. Philips was one of the companies that they initially collaborated with to design it. Plans for the device were scrapped, but Phillips walked away with contractual rights to produce games with Nintendo licensed characters. Three Zelda games and a game entitled Hotel Mario were released for the Philips CD-i. However the games were not produced by Nintendo and were considered lackluster (ok more like terrible). |

|

|

by Marriott_Guy |

|

|

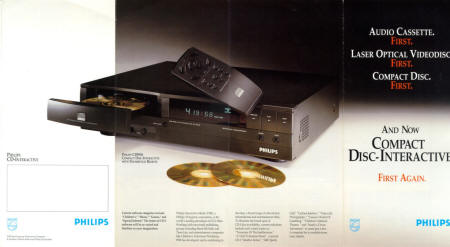

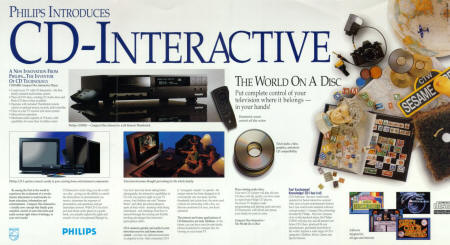

In the late 1980s, the Compact Disc had become the preferred format for delivering both audio recordings (CD-DA) and personal computer

applications (CD-ROM). Though the advancements in both quality and quantity that was afforded by this new media format were

undeniable, the cost to take advantage of this new technology was steep and usually involved upgrading multiple devices. There

was also the small fact that the central point of most living rooms - the television - was not able to deliver any of this enhanced

content. Compact Disc Interactive (CD-i) was developed to be the solution. The CD-i format was established during the mid 1980s in a joint venture between Philips and Sony (who also partnered to create the CD-DA and CD-ROM standards). This framework enabled pictures, audio, video and interactive program content to be delivered simultaneously from a single compact disc, which then could be transmitted to your television via a dedicated unit - the CD-i player. |

|

|

CD-i based systems were not intended to be pure gaming consoles - entertainment titles were meant to be just a part of the overall

experience. CD-i provided the canvas for a variety of applications, including edutainment software and full length movies.

At its launch in 1991, the system was not even displayed in stores with the other video gaming systems of the time (Sega Genesis,

Nintendo SNES, etc.). It was promoted within its own area, closer to the personal computer section. This exemplifies one

of the primary reasons for the downfall of the CD-i - indecisive marketing. Philips had the unenviable task of educating the consumers while at the same time marketing a high-end product and its multiple benefits. Philips invested heavily into advertising the CD-i through print as well as television via infomercials (a first for any system). Regardless of the media vehicle, the message was the same - what exactly is this device? Is it a gaming machine? A replacement for the personal computer? An upgrade to the VCR? There were entirely too many unanswered questions regarding the CD-i for any gamer to cough up a significant chunk of their life savings to obtain one of these at launch - $699 USD. This high price tag was definitely a deterrent for both gamers and those looking to upgrade existing devices. The initial design, and redesigns, of the CD-i reiterated this somewhat waffling approach. |

|

|

|

|

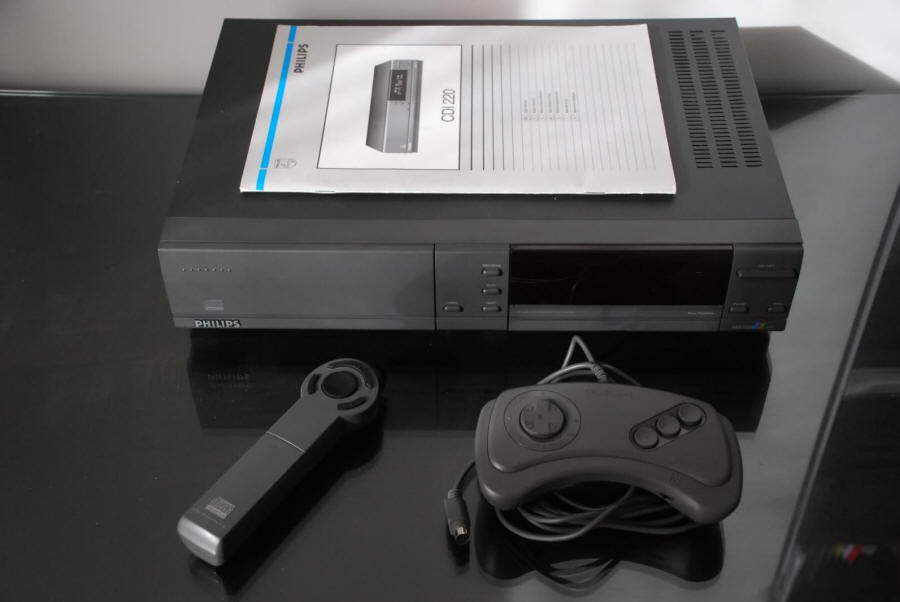

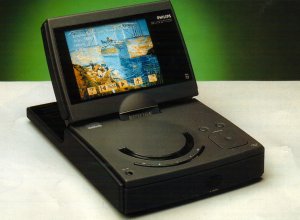

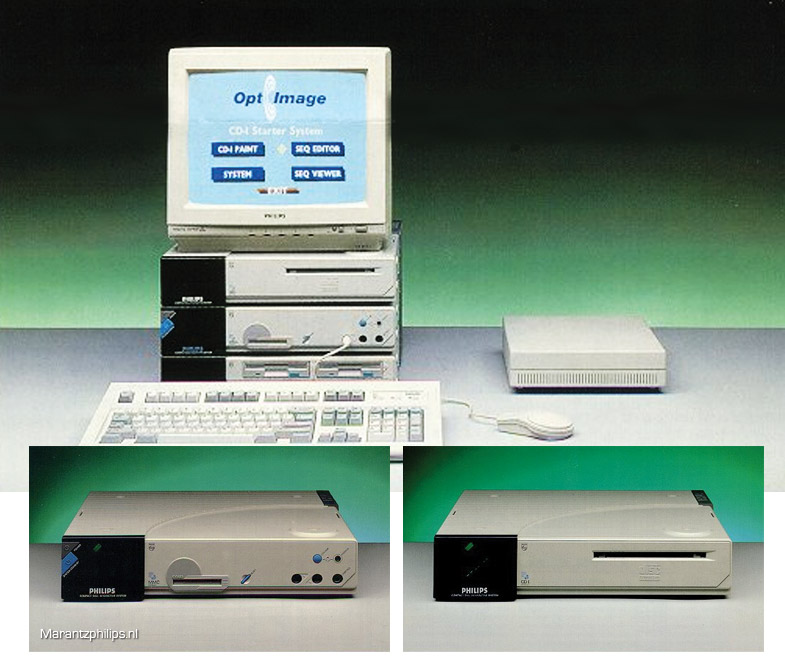

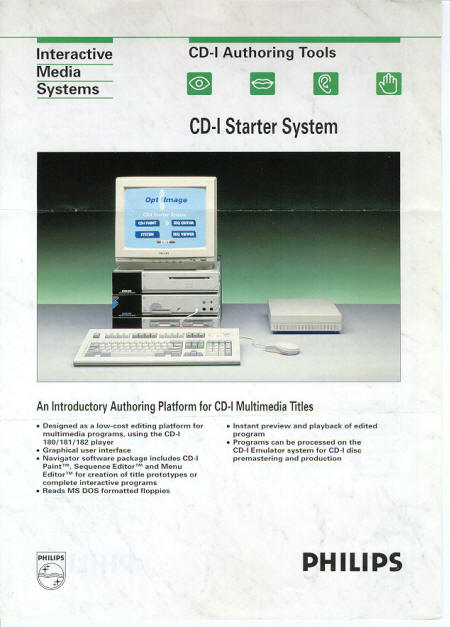

The initial chassis of the CD-i (model CDI 205 Europe \ CDI 910 North America) was designed to be accommodated within a standard AV

rack measuring 16.5" x 3.5" x 15.75" (42 x 9 x 40 cm). The matte black casing was very sleek with the uncluttered facing

utilitarian yet highly functional. Crisp, large LED lighting communicated system status messages to the user. Front access

to basic ports was also a nice touch. Overall, the design is rather minimalistic yet sophisticated and fits in seamlessly with

other AV devices. Later models would vary in color (primarily black, white and grey) with some sporting a more 'video game

system' look (i.e. the CDI 450 model). Regarding technical specifications, all CD-i systems needed to conform to a minimum base configuration: 68000 (or similar) CPU at 15.5 MHz, 1 MB of RAM, 8 KB NVRAM, dedicated audio/video processing chips and CD-RTOS (Compact Disc Real Time Operating System). All CD-i models are able to play Audio CD (CD-DA), CD + Graphics (CD+G), Video CD (VCD) and Kodak Photo CD. Consumer models varied with some including more bells and whistles than others, but the key difference was the inclusion, or lack thereof, of the Digital Video Cartridge. |

|

|

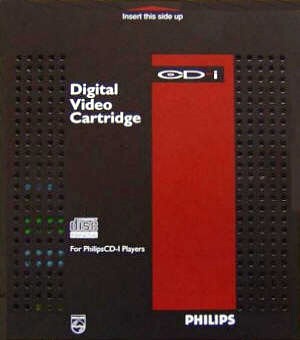

The Digital Video Cartridge (DVC) enabled playback of CD-i movies as well is required by a great number of software titles. The

initial run of CD-i players provided a port to accept the optional DVC, while later models included this technology directly.

Philips released two different versions of the DVC - the 22ER9141 and the 22ER9956. Both were identical in performance but

differ in size to accommodate respective players (compatibility

chart here). The DVC also provided an additional 1 MB of RAM for system use which greatly improves overall performance

across the board. The DVC (or embedded technology) is basically required to maximize the CD-i experience, including game play. The CD-i software library consists of approximately 625 total titles, 124 of which are games. There are many exclusive offerings for this system and quite a few hidden gems, but overall the collection was rather weak in terms of game quantity and quality as compared to the contemporary systems that focused entirely on gaming. Interacting with these titles was also a chore. Early CD-i systems did not come with a standard gamepad, but were accompanied with a multifunctional IR remote (CD-i Thumbstick - pictured above). The remote is pretty worthless when it comes to gaming. Later systems were packaged with the wireless CD-i Commander, which featured pressure sensitive response in a rather generic 4 button casing. Other optional peripherals include keyboards, gamepads, light gun, mice and roller controllers specifically designed for children. Overall, interacting with the CD-i is rather cumbersome from a game play perspective. |

|

|

The CD-i was a very advanced system for its time, one of the first to truly deliver a multimedia experience via a single device

through your television. It received support from many major manufacturers including Sony, LG (GoldStar), Memorex and Bang &

Olufsen. In total, over 40 different models of the CD-i system were produced - the most of any video game system that has ever

been released. The CD-i still enjoys a cult-like following, with many websites devoted to continued software development and

other facets of this machine. Where it faltered was in its chameleon-like approach to marketing. Trying to be everything to everybody has never worked when it comes to electronics, especially while having the burden to educate the general public on new technology. Even after switching gears and marketing the CD-i as a video gaming machine, the message was still cloudy at best for the consumer. Philips has always been a leader in developing new technology. The CD-i is a perfect example of this, but missed the mark when identifying and targeting its audience. |

|

|

|

|

2010s - NOTES

2010s - NOTES

MODELS

MODELS

CLONES

CLONES CONSOLE RATINGS

CONSOLE RATINGS

FORMAT, PACKAGING & GENERAL INFO

FORMAT, PACKAGING & GENERAL INFO

SCREENSHOTS

SCREENSHOTS

EMULATION

EMULATION

SPECS & MANUALS

SPECS & MANUALS OTHER

MEDIA

OTHER

MEDIA

WEB RESOURCES

WEB RESOURCES

DISCUSS

DISCUSS