History - Video Game Crash of 1983

by Daniel A. Mazurowski with added content from Dark Watcher |

|

At its height in 1982, the video game industry employed hundreds of thousands of people and generated over two

billion dollars in sales. And then, unexpectedly, it all collapsed, virtually overnight. What happened? How could an industry so large, fail

so quickly, so completely, without any obvious calamity to cause its downfall? There were three major factors, none of them significant enough

on their own to do more than moderate damage. But combined, they proved to be fatal. |

|

The Game Glut |

In the early '80s, dozens of companies were rushing into the game cartridge business. Heck, even Quaker Oats had a game software

subsidiary. The impressive success of the first two third party cartridge companies, Activision and Imagic (both started by

former Atari programmers) dazzled accountants across the country - low start-up costs, accompanied by large mark ups, meant huge profit

potential.

But these new game makers did not understand their own products. "A video game was a video game," they thought.

"Just clone a known formula and it'll sell." Millions of dollars were squandered on licensing fees to get recognizable characters, assuming

name recognition was more than enough to carry a mediocre game. (Well, sometimes it was. Remember Nintendo's

Popeye?) Quality control and play testing were virtually non-existent. Programmers were held to strict deadlines to keep costs down,

stifling creativity and experimentation. As a result, an amazing quantity of low quality me-too titles were dumped into the marketplace,

manufactured with little regard for how many units may realistically be in demand.

So people got tired of buying. How many Pac-Man clones could you play before the charm wore off? How many half-baked,

bug-ridden cartridges would you plug into your system before you started to feel burned? Consumers were staying home in droves.

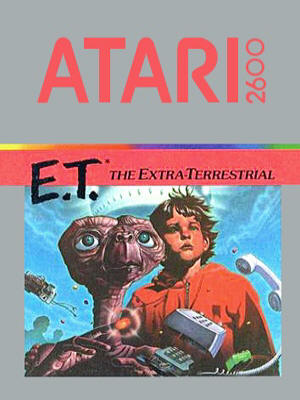

But the newcomers weren't the only guilty parties. In their rush to snap up arcade titles, Coleco paid

little attention to quality. For them, it did not matter if a game was good or not, it simply had to be an arcade title. Atari

squandered millions to license titles and characters such as E.T., only to develop a poor title in massive quantities. (Atari

reportedly buried millions of unsold cartridges in an unmarked desert landfill in 1984.) And

Mattel generally over-produced all their titles, in anticipation of continually increasing future demand that never materialized.

|

|

|

The Computer Price Wars |

In 1980, a capable home computer was a fairly expensive investment. At that time, a brand new Atari 800, new on the market and one of

the most affordable machines available, would set you back $800. And that was just the computer - no disk drive, printer, or monitor. But that

would change very quickly.

Two years later, Commodore Business Machines introduced its most advanced home computer to date - the Commodore 64. In many ways

it was technologically inferior to systems already on the market. It had only 16 colors which could not be altered. The voice chip was only

capable of three voices. Disk access was painfully slow. The closed architecture, coupled with the non-standard I/O connector, made

expansion a hassle. But the computer was CHEAP. People could finally afford to be a part of the computer revolution.

What ensued over the next few years was a bloody price war among the various home computer companies, with the exception of Apple. A

dozen or more computer makers slugged it out, only two survived -

Commodore and Atari. And they were severely bloodied by the experience. When it was all over, a decent computer could be had for

$150, and entry level machines were well under the $100 mark.

So now consumers had to ask, why buy a game machine when I can get a computer for just as much? Computers had graphics and sound at least as

good as the newer home game systems, some times even better. And they were capable of playing more sophisticated games than the game consoles. Of course, computers were also more practical, since they could do things other than games.

Still, it wasn't long before people realized there actually was a reason to own both a computer and a game machine. "Let the kids play with

the game system while I am using the computer." But by this time, all the big players were out of the game. Atari was under new

ownership (bought by Jack Tramiel, former Commodore CEO from

Warner Communications) and out of the game business (well, temporarily anyway). Mattel and Magnavox had both shut down

their game operations. Coleco was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, with its popular Cabbage Patch Dolls the only thing

keeping the toy maker solvent. The cartridge and accessory manufacturers were either bankrupt or moving to the computer business - as software

makers or building peripherals. When the public was finally ready to accept game machines again, the only system on store shelves was the

Nintendo Entertainment System. With no competition, Nintendo

soon moved to center stage and dominated the industry with an iron hand through the remainder of the '80s.

|

Atari 800

Commodore 64 |

|

Consumer Apathy |

In 1983, the video game industry was 11 years old. In its infancy, there had been only the Pong-type game consoles on the market. They

were a popular diversion, but failed to capture the consumer's imagination. Then in 1976, the first programmable system appeared on the scene

and it was suddenly a whole new ball game. With the paddle-and-ball machines you only had four or five game variations built into the console,

with little changing from one game to the next. But now you could buy new, completely different games for your system when ever you got tired

of what you already had. The possibilities were literally endless. Consumers went on a buying frenzy of consoles and game cartridges,

particularly in the case of Atari's 2600.

As the industry continued to evolve, things changed. New systems appeared every year. Many either failed quickly

or clung to life in obscurity, but a few garnered a respectable chunk of market share. With each new machine came new innovations, new

ways of doing things, coupled with a new level of confusion for the consumers. What features do I really want? What features were nothing but

techno-babble nonsense meant to impress the unwary buyer? And what software from which companies would work on my console?

By 1982, the situation was escalating at a pace that was out of control. New buzzwords were being invented by

the software and hardware companies every week. Store shelves were getting crowded, with over ten different systems on the market and

manufacturers promising even more in the next two years. Consumers had finally had enough. No sooner would one system be hailed as the

ultimate in gaming hardware before another would appear to take its place. Many simply decided to wait and see which machine out of this flood would

become dominant prior to any purchase.

It was a vicious cycle that could not be broken. Older systems had reached the point of saturation so further

sales would be low at best. New systems had the features consumers wanted, but with old consoles selling so slowly, companies were reluctant

to invest capital on R&D. The new systems that did appear required enormous marketing expenses just to be noticed by the public. These systems

suffered from small game libraries, in part because of the new technology and because so much was spent on marketing that there was little

left for game development. Nothing manufacturers tried could lure enough consumers into the stores to sustain the industry. As console and

cartridge sales plummeted, machines in development were cancelled and in the end everybody withdrew from the marketplace - either by choice,

as Mattel did, or forced out by near bankruptcy like Coleco.

|

|

|

DISCUSS

DISCUSS